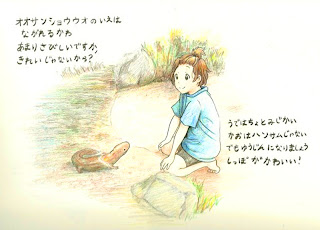

ビシャンバシャン, "splish, splosh" , Children's Book“泳げカメレオンくん” / “Chameleon Swims”

マグネシウム, "Magnesium", scientific journal, Tokyo Kagaku Kaishi

The modern Japanese language consists of three types of script: kanji, hiragana, and katakana. Early Japanese language consisted entirely of kanji adopted from Chinese around the 5th century. Over time, the language evolved by assigning different readings to these Chinese characters, creating the –on and –kun readings that still exist in the Japanese language today. Katakana and hiragana, however, did not develop until the onset of the Heian period, around the 9th century. At this time, the study

of Buddhist texts written in Chinese was becoming popular among monks. Katakana originally developed as a sort of mnemonic shorthand for writing the often complex characters quickly and in a more simplified manner. Hiragana also developed at this time, and was regarded as a more aesthetically pleasing sort of cursive script. Of course, all three scripts are still used today, but one can arguably observe an ever-increasing amount of katakana being used in modern texts (Igarashi 16-22)

Upon considering the uses and function of Katakana in modern Japanese writing, one finds a number of opinions regarding the definitive use of the script. Indeed, a variety of definitions can be found across Japanese language textbooks. Yuko Igarashi presents what seems to be the most widely excepted definition in her paper entitled “The Changing Role of Katakana in the Japanese Writing System:

Processing and Pedagogical Dimensions for Native Speakers and Foreign Learners”. The description involves the categorization of Japanese words into three distinct groups, each of which is generally associated with one of the three scripts. The first of two of these categories, “kango”, which includes Sino-Japanese words (words derived from Chinese), and “wago”, or Japanese native words, generally correspond respectively to kanji and hiragana. The third classof words, “gairago”, are thought of as ‘loanwords’ to the Japanese language. However, katakana is unique in the sense that it can be used unconventionally in the place of both wago and kango for the sake of emphasis, onomatopoeia, or as an indicator of a unique speech pattern unlike the in the rest of the text (Igarashi iii-iv).

The first phrase that I chose came from a children’s book: “ビシャン、バシャン” (“splish, splosh”). Onomatopoeic phrases like it are usually written in katakana, and there are certainly a lot of examples in the list that the sum of our classes has generated. It is not difficult to understand why onomatopoeias would be written in this special script - katakana separates them from the rest of a sentence to the same effect as capitalizing, italicizing, or adding an exclamation mark would do in English. Indeed, this particular use of katakana is often compared to italicization. The katakana script also indicates text that could have been said in an unusual way, for example, in a more elevated tone, different from the normal speech that borders it. In Japanese, the text not only differs by slant or boldness, but also by alphabet, which in effect separates it not only from the rest of the text, but also from the rest of the language. Sound words, which are often made-up, nonsensical ‘words’, seem to be less of an actual part of the Japanese language if they are written in katakana. In this way, the original language is preserved.

The definition common to most textbooks, it seems, involves, at the least, the description of katakana as the script used for loanwords(aside from those from Chinese) and foreign names. This is because this is the major usage of katakana, especially in contemporary writings. Many would argue that there is an ever-increasing amount of gairago finding its way into modern Japanese, and for each of these words, a Japanized version emerges, written in katakana. The list is extensive, as evidenced by the dozens of different loanwords that have been donated to our class list. What I found interesting was that the scientific journal article that I found, from Tokyo Kagaku Kaishi, presented the words for the elements in katakana (i.e. magnesium = マグネシウム, calcium = カルシウム, etc.) as opposed to kanji. The names of minerals and scientific names of plants and animals are written in katakana, which often come from Latin. If one looks at a timeline of the discovery of the elements, one finds that most elements discovered (roughly) before the 13th century generally have their own in kanji script (i.e., gold (金), and copper (銅)), whereas most of the more recently discovered elements, certainly those discovered after the 18th century, such as uranium – “ウラン” (1841), magnesium (1808), calcium (1808), etc. are written in katakana. The elements discovered between the 13th and 18th century are a mixed bag, with the most important written in kanji, i.e. hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and chlorine (all discovered during the 1760s-1770s). I am not sure what exactly to attribute this phenomenon to except perhaps the exponential expansion of science in more recent times, and the relative obscurities of some elements to others (for example, oxygen is far more often referred to than, say, dysprosium, therefore it would make sense to assign it its own kanji which will be recognized often). This, however, is just speculation and much more research would be required in order to determine a more concrete answer.

Katakana usage often seems arbitrary, especially when looking at scientific words and other loanwords. I’m sure this is why textbooks have difficulty coming up with a set definition. They may want to prevent readers from assuming that the rules regarding katakana usage are set in stone.

Links to sources:

“The Changing Role of Katakana in the Japanese Writing System:

Processing and Pedagogical Dimensions for Native Speakers and Foreign Learners

Elemental Discovery Timeline